[---][center]

[large]Tom Watson

The Official Record in the Case of Leo Frank, a Jew Pervert[/large][/center][---]

Published by Editor on March 19, 2014

http://theamericanmercury.org/2014/03/t ... ew-pervert

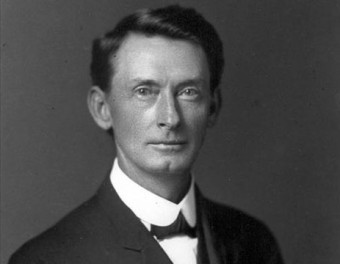

[justify]by Thomas E. Watson (pictured), Watson?s Magazine, Volume 21 Number 5, September 1915

IN NEW YORK, there lived a fashionable architect, whose work commanded high prices. He was robust, full of manly vigor, and so erotic that he neglected a handsome and refined young wife to run after little girls.

As reported in the papers of William R. Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer, and Adolph Ochs, the libertine architect had three luxurious suites of rooms fitted up for the use of himself, a congenial company of young rakes, and the young women whom they lured into these elegant dens of vice.

Stanford White?s principal place, however, was in the tower-apartments of Madison Square Garden. In this building, his preparations for sensual and sexual enjoyment were as carefully elaborated and as expensively perfected, as though wine, women and song were the chief end of man?s existence. The excavations at Pompeii have revealed no Rose-door voluptuousness more Oriental than that of Stanford White. Like the Roman sensualist who stimulated his amorous passions by surroundings that promoted desire and prolonged the pleasure, White was artistic in his vices; and it was the nude girl, of perfect symmetry and beautiful face, that he bore into his seraglio, where rich and splendid appointments, soft lights, hidden musical instruments, fragrant flowers, and choice wines intoxicated every sense to the highest pitch of epicurean ecstasy.

Into this golden harem, he took the young, lovely and unmoral Evelyn Nesbit; and, according to her statement, she was brutally used. A shocking fact in the case is, that White seems to have given money to the girl?s mother, and that the mother had, in effect, surrendered the maid to the man?knowing why he wanted her.

Whatever the girl felt as to the manner in which White had accomplished his purpose, she soon afterwards returned to him, and their relations continued for some months. Then Harry Thaw happened to see her, fell in love with her, and desired so ardently to possess her, that he married her.

They went to Europe, and during the tour, the wife told the young husband her terrible story. On their return to New York, the architect had the insane folly to again enter into correspondence with Evelyn?this time knowing that he had an excitable young man to encounter?a husband who might be supposed to have learned his wife?s secret. All the world knows how Thaw was inflamed beyond bounds, by seeing White sitting in the eating-room, at the Garden; and how the young husband immediately shot the satyr who had doped and ruined his wife.

The great legal battle that Thaw?s devoted mother has waged in her boy?s behalf, is a part of the history of the times. For nine long years, that fine old woman has borne her cross, and made her fight, her son behind the bars, all those bitter years.

At last, after nine years of imprisonment, Harry Thaw is a free man?for the court which tried him for murder, pronounced him insane; and the jury which recently tried him for insanity, said that he is sane.

At least one of these verdicts was correct, and both may have been; but the jurors in the last trial have since declared that Thaw ought to have killed White, anyway; and about three-fourths of the red-blooded men and women of the country are of the same opinion.

But the Jew-owned papers, and the Jew-hired papers, and the Hearst papers take a different view. They are outraged. Their feelings are deeply hurt. They lament the failure of the Law to hang this hot-tempered boy who shot the man that had virtually bought Evelyn from her monstrous mother, and had then drugged and forced her. In their wrathful eyes, nine years? imprisonment is no punishment at all. They rail at the influence of Money, and deplore the disgrace which has fallen upon New York?the righteous town where Jacob Schiff, the banker, could give a forty-year sentence to an humble Jew, for entering clandestinely the dwelling of a Jewish millionaire; the righteous town wherein the Roman priests could have the Mayor assassinated without provoking hostile comment from the Hearst papers, the Jew-owned papers, or the Jew-hired papers; the righteous town where the priest, Hans Schmidt, can cut his concubine?s throat, dismember her body, fling the pieces in the river, and still escape punishment!

Let us regale our minds by reading what the Hearst papers say about the case of Harry Thaw:

It is quite true that but for the lavish outpouring of the family fortune, Thaw might have been electrocuted, or would still be confined in a madhouse. It is equally true that but for the contributions of other rich young men, whose money cursed them, his fight for liberty would not have been so prolonged or so costly.

Many will moralize over the power of money as manifested in the escape of Thaw from paying the extreme penalty for the murder of Stanford White.

Fewer will stop to think of the malign power of money that pressed this rich young man along the primrose path that ended in the murder on the roof garden, his prolonged imprisonment, and the ineradicable disgrace which rests upon his name.

As it is, about the most the public can say of him is to express the hope that the public mind shall not longer be assailed by the fulminations of spectacular lawyers, the imaginings of alienists, and the bathos of hired pamphleteers. The world is weary of Thaw.

The world is not weary of Hearst, fortunately; and if he can explain his prolonged hostility to Thaw, and reconcile it with his determined championship of Frank, the world will peruse his statement with interest.

Let us now read what another New York paper?Jew-owned or Jew-hired?published about the two cases, Frank?s and Thaw?s. Concerning Thaw, the New Republic says:

In the case of Harry K. Thaw, it looks as if the State of New York had thoroughly well got its leg pulled. The State deserved it richly, for it asked a judge and a jury to decide a question which they are simply incapable of deciding. Those laymen could no more pass on Thaw?s sanity than upon the condition of his liver. Thus a man may be highly educated, courteous, genial in every relation of life, and still bear within him a murderous disposition, which breaks out only on special occasions. The voluble juryman who has been so much interviewed came pretty close to the truth when he said that Thaw would never kill except when a woman was involved.

What freed Thaw was in reality a combination of prejudices. He behaved well in court. The State?s alienists behaved badly in court. Thaw fought a long fight, and men admire persistence. He had murdered Stanford White, a man who happened to be a genius, but whose genius was forgotten in the deep moral prejudice against him. The brutal fact is that an American jury is very ready to flirt with the idea that there are unwritten laws to justify the killing of men who seduce young girls.

Concerning the Frank case, the same New York paper says:

It is often too foolish to indict a whole people. But in this instance the guilt of the people is clear. They wrecked the only trial Frank has had, they believed every lie about him, they terrorized their public officials. They have made democracy hideous?they, the men and women of the State. There was a minority that knew better, a minority that did not wish to make the courts of the State a vile spectacle to the whole nation. But of that minority many were too cowardly to speak out. They allowed the mob to stamp its own imprint upon the public character of the State. The Governor who acted, and the opinion which supported him, were not enough to save Georgia from its degradation.

A people which cannot preserve its legal fabric from violence is unfit for self-government. It belongs in the category of communities like Haiti, communities which have to be supervised and protected by more civilized powers. Georgia is in that humiliating position today. If the Frank case is evidence of Georgia?s political development, then Georgia deserves to be known as the black sheep of the American Union.

It is a disagreeable discovery of the New Republic, that American juries harbor a perverse sympathy for fathers and brothers who kill the seducers of young girls, and thus rid the earth of the most dangerous vipers that crawl. The New Republic says that it is not only a fact that juries do sympathize with the men who give shot-gun protection to womanhood, but that this fact is brutal.

When the human race ceases to be capable of brutality of that sort, civilization will be the soup-kettle of molly-coddles; and literature will degenerate into a milk-sop effeminacy that won?t be worth hell?s room.

Coming to the Frank case, the New Republic condemns, not only the jury and the judges, but the whole State in which the horrible crime was committed. ?It is often foolish to indict a whole people,? says this magazine. Edmund Burke said it was always foolish to do so.

The State of Georgia, as a whole, is pronounced guilty. It has had no evidence against Frank; it has been possessed of a Devil of blind hatred; it has relentlessly persecuted; it has tried to lynch an innocent man, under legal forms. Its mobs terrified the witnesses; terrified the jurors; terrified the trial judge; terrified the Supreme Court of Georgia in both of its decisions, the last of which was unanimous. Finally, the Georgia mobs terrified the Supreme Court of the United States, which, under duress, decided that Frank?s lawyers?after having had all the time, money and opportunity needed?had utterly failed to show that Georgia had not given to Leo Frank every right to which he was entitled.

What do such editors care for the calm decision of the highest court on earth? Nothing.

?The guilt of the people is clear.?

?They have made democracy hideous.? Where? When? And how?

When justice was mocked in San Francisco, some years ago, and William T. Sherman (afterwards the great General) led the ?mob,? did the riotous tumults of an indignant democracy make it hideous? When justice was derided and defied in New Orleans, and the outraged democracy flamed into a vengeful conflagration, did it become hideous?

When our Revolutionary Fathers lynched Tories, and drove traitors into hasty flight, did they make democracy hideous?

When the Commons of old England rose in bloody riots against the Lords of Church and State, during the Epoch of Reform, did these insurrectionary Englishmen, battling for human rights, make democracy hideous?

When the Athenians of old furiously fell upon and killed the Greek who advised that Grecian freedom be surrendered to the Persian King, did those rioters make democracy hideous?

Away with milk-sops and molly-coddles! Whenever the human race degenerates to the point where intense indignation is not aroused by enormities of crime, then mankind will be ready for the last Fire; and the sooner this scroll is given to the Flames, as the trump of doom sounds the requiem of a dying world, the less will be the sum total of human depravity.

In Georgia, there was never a mob collected while the Frank case was on trial; never a scene of tumult, never a disorder in the court room. It was not until after the State had patiently waited for two years, while the unlimited Money back of Frank was interposing every obstacle to the Law, travelling from court to court, on first one pretext and then another; offering new affidavits which soon appeared, confessedly, to have been falsehoods, paid for with money; resorting to every criminal method to corrupt some of the State?s witnesses, and to frighten others into changing their testimony; it was not until the people of Georgia had waited so long, and seen Frank?s lawyers defeated at every point, by the sheer strength of the State?s case against a most abominable criminal; it was not until, after all this, when one of Leo Frank?s own lawyers basely betrayed the State, upset all the courts, and violated our highest law; it was not until John M. Slaton, the partner of Leo Frank?s leading lawyers, corruptly used the pardoning power to save his own guilty client?it was not until then that the people broke into a tumult of righteous wrath against the infamous Governor who had put upon our State this indelible stain.

And because our indignation took the same direction as that of our Fathers, in the days of ?76; the same direction as that of the Frenchmen who stormed the Bastille; the same as that of the Englishmen who sacked the Bishop?s palace, and the nobleman?s castle; the same as that of the Viennese who rose in fury against the Emperor and his Metternich, forcing that crafty and coldly ferocious old democracy-hater to flee for his life?because of the fact that we Georgians are just human, we must be relegated to a San Domingo basis, and treated by other States as though we were woolly-headed worshippers of Vaudoux!

HOW ABOUT BECKER AND NEW YORK?

The Becker case created a profound and painful impression everywhere, because of its contrast to the case of Leo Frank. The Hearst papers, the Jew-owned, and Jew-hired papers, have found this contrast embarrassing to them, and they are endeavoring to ?distinguish the cases.?

For example, the New Orleans Daily States says:

A patient perusal of all the mass of evidence, considered in the light of the clashing interests of those involved, directly and indirectly, in the Rosenthal tragedy, has left us unconvinced that the law?s reasonable doubt of Becker?s guilt was removed. That Becker was a police tyrant and grafter, was amply proved. The fact that he was more or less endangered by Rosenthal?s promised revelations of police corruption furnished a motive which made it easy for others who confessed they were in the murder plot to fasten the crime on him. But there will always be ground for the suspicion that the Rose-Webber crowd ?framed? Becker to insure their own immunity.

But whereas Frank was denied the safeguards and privileges which the State pledges any person accused of a capital crime, and was convicted in a community rank with prejudice and mob spirit, on the testimony of a vicious negro criminal, Becker was robbed of no technical right the law guaranteed him.

Few more deliberate and cold-blooded murderers have been committed in New York than the assassination of Rosenthal, and public sentiment was powerfully exercised against Becker in the face of clear evidence that he was a grafter with a motive for sealing Rosenthal?s lips. But it would be absurd to liken the atmosphere in New York during the Becker trial to that in Atlanta during the Frank trial, or to find any points of resemblance between the orderly conviction of Becker and the utterly disorderly trial of Frank.

So! Another case of my bull and your ox. Do we not all remember that when Bourke Cockran moved for a continuance in the Becker case, and Judge Samuel Seabury refused it, the great lawyer threw up his brief, and passionately exclaimed, ?This is not a trial; it is an assassination??

No lawyer said that to Judge Roan, trying Frank; and there never was the slightest evidence that Frank?s trial was ?disorderly.?

The Daily States asserts that ?Becker was robbed of no technical right the law guaranteed him.?

Does the States know that the U.S. Supreme Court used those very words in the case of Frank?used them in a well-considered decision, which is the amplest vindication of the Georgia courts?

When the highest court in the world judicially affirms that the State which tried and convicted Frank accorded him every right guaranteed to him under the highest law, ought not the decision to be respected?

Before the United States Supreme Court vindicated Georgia, the agencies working for Frank expressed the most exultant confidence in the outcome of the appeal; and declared that, at last, the case had reached a tribunal which would not be influenced by ?mob frenzy, psychic intoxication, jungle fury,? and the rest of it.

After the United States Supreme Court patiently heard Frank?s lawyers, and solemnly assured ?mankind? that the State of Georgia had not been shown to have denied Frank any legal right, was ?mankind? satisfied? By no means. ?Mankind? gasped in silence a few days, and then broke out into a more furious roar than ever, just as though the highest of courts had not decided the case in our favor.

It must have cost ?mankind? millions of dollars to lynch the Georgia courts, with outside mobs.

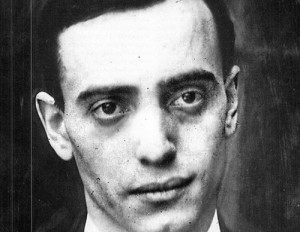

Frank ?was convicted on the evidence of a vicious negro criminal.? So says the Daily States, saying it, not because it is true, but because all the other Frankites say it. Without the negro, James Marshall, Becker could not have been convicted, and the highest New York court so held. Whether James Marshall is a criminal, I do not know; but the official record in the Frank case shows that Jim Conley was never a criminal until he became the accomplice of his master, Leo Frank.

May I ask the Daily States to take my word for it, that the law of Georgia does not allow any man to be convicted on the testimony of an accomplice?

The so-called vicious negro criminal was confessedly the accomplice of Leo Frank; and therefore the law made it necessary for Solicitor Dorsey to practically make out the whole case against Frank, without relying at all upon the negro?s evidence.

When that miserable little Jew jackass, Clarence Shearn, of the New York Supreme Court, was sent by his owner, Mr. Hearst, to review the record in the Frank case; and when he wrote an opinion in which he stated that there was no evidence against Frank, save that of the accomplice, he virtually charged our Supreme Court?as well as Judge Roan?with having violated their oaths of office.

Little Shearn does not know enough of Georgia law to be aware of the fact that nobody can be convicted on the evidence of an accomplice; and that, under our Supreme Court decisions, such evidence is almost valueless. The case must be made out independently of the accomplice, to well-nigh the same extent as though he had not testified.

This being the law in Georgia, how can editors who wish to tell the truth, continue to say that Frank was convicted by his accomplice?

Assuming that the great majority of the American people want to know the truth, and want the law enforced wherever crime is proved, I invited every fair-minded reader to come with me as I go into the official record?a summary of the sworn testimony, agreed on by the lawyers for both sides, and sanctioned by the trial judge.

But before turning to the dry leaves of the Brief of Evidence, let me ask you to look upon the girl herself, as she appeared in life to one who seems to have known her well. Writing to The Christian Standard, in protest against an editorial in the Christian-Evangelist, A.M. Beatty says:

Mary Phagan was a member of the Adrial class of the First Christian Bible School, and the last act she did on earth was to iron with her own hands her white dress that she might present the next day and help in winning a contest. The Sunday she expected to be at Bible School she was lying on a slab in an undertaker?s in the same block as the First Church is located, having met death in a horrible manner.

It is very complete?that little picture, drawn in two sentences. Mary Phagan, not quite 14 years old, ironing the white dress she meant to wear to the Bible school, the next day. The First Christian Church stands near the morgue, and as she day-dreamed of the morrow, and the contest in her class, she saw the temple, and the white-dressed girls who would be her companions: she did not see the morgue.

The pity of it! The garment which she washed and ironed became her shroud, after she had been to the morgue, instead of to the church! Surely, fate has seldom been more cruel to a perfectly innocent child.

Mrs. J.W. Coleman was the first witness for the State. She testified:

?I am Mary Phagan?s mother. I last saw her alive, on April 26th, 1913. She was getting ready to go to the pencil factory to get her pay envelope. About 11:30 she ate some cabbage and bread. She left home at a quarter to twelve. She would have been fourteen years old on the first day of June. Was fair complected, heavy set, very pretty, and was extra large for her age. She had dimples on her cheeks.?

(Witness described how her daughter was dressed, and identified as Mary?s, the articles of clothing shown her?clothing taken from the corpse.)

George Epps, a white boy, was the next witness. He was fourteen years old, and was neighbor to Mary?s family. He rode on the street car with Mary as she came into the city. She told him she was going to the pencil factory to get her money, and would then go to the Elkin-Watson place to see the Veterans? parade at 2 o?clock. ?She never showed up. I stayed around there until 4 o?clock, and then went to the ball game.

?When I left her at the corner of Forsyth and Marietta Streets?she went over the bridge to the pencil factory, about two blocks down Forsyth Street.?

The boy put the time of his separation from the girl at 12:07, but on cross-examination, he said, first, that he knew it by Bryant Kehelye?s clock, and then, by the sun.

(The immateriality of the variations in time, except on Leo Frank?s own clock, will be shown directly.)

The next witness for the State was Newt Lee, the negro night-watch at the factory. He had been working there only about three weeks. Leo Frank had taken him over the building, and instructed him in his duties. On every day, except Saturdays, he was to go on duty at 6 o?clock p.m. On Saturdays, at 5 o?clock.

On Friday, the 25th of April, Frank said to Newt, ?Tomorrow is holiday, and I want you to come back at 4 o?clock, I want to get off a little earlier than usual.?

Newt then went on to say that he got to the factory on Saturday about three or four minutes before four. The front door was not locked; he had never found it locked on Saturday evenings. But there are double doors half way up the steps, which he had always found unlocked before, but which, this Saturday evening, he found locked.

He took his keys and unlocked this stair-way door, and went on up-stairs to the second floor, where Frank?s office was.

Newt announced his arrival, as he had always done, by calling out, ?All right, Mr. Frank!?

?And he come bustling out of his office,?and says, ?Newt, I am sorry I had you come so soon; you could have been at home sleeping. I tell you what you do; you go out in town and have a good time.??

Newt stated that always before when Frank had anything to say to him, he would say, ?Step here a minute, Newt.?

This time, Frank came bustling toward the negro, rubbing his hands; and when Newt asked to be allowed to go into the shipping room to get some sleep, Frank answered, ?You need to have a good time. You go downtown, stay an hour and a half, and come back your usual time at 6 o?clock. Be sure to come back at 6 o?clock.?

Newt did as he was told, returned to the factory at two minutes before six, and found the stair doors unlocked. Frank took the slip out of the time-clock and put in a new one.

?It took him twice as long this time as it did the other times I saw him fix it. He fumbled, putting it in.? After the slip had been put in, Newt punched his time, and went on down stairs.

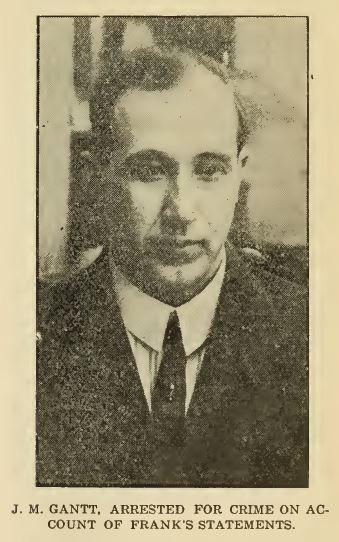

Mr. J.M. Gantt came to the front door and asked Newt for permission to go up stairs after an old pair of shoes he had left there, some time before when he was employed at the factory. Newt answered that he was not allowed to let anyone inside after six o?clock.

?About that time Mr. Frank came bustling out of the door, and ran into Gantt unexpected, and he jumped back frightened.?

Gantt asked Frank if he had any objection to his going up stairs after his old shoes.

Frank answered, ?I don?t think they are up there. I think I saw a boy sweep some up in the trash the other day.?

Gantt asked what sort of shoes he saw the boy sweep out, and Frank said they were ?tans.?

Gantt replied, ?Well, I had a pair of black ones, too.?

?Frank says, ?Well, I don?t know,? and dropped his head down, just so??illustrating.

?Then, he raised his head, and says, ?Newt, go with him and stay with him, and help him find them.? And I went up there with Mr. Gantt, and found them in the shipping room, two pair, the tans and black ones, too.?

That night, after seven o?clock, Frank telephone to Newt, and asked, ?How?s everything??

That was the first time he had ever phoned the night watch on a Saturday night. He did not ask about Gantt.

There is a gas jet in the basement at the foot of the ladder, and Frank had told Newt to keep it burning all the time.

?I left it Saturday morning burning bright. When I got there, on making my rounds at 7 o?clock p.m. on the 26th of April, it was burning just as low as you could turn it, like a lightning bug. When 3 o?clock came? (after midnight, of course,) ?I went down to the basement?.I went down to the toilet, and when I got through I looked at the dust bin back to the door? (the back door opening on the alley) ?to see how the door was, and it being dark, I picked up my lantern and went there, and I saw something laying there, which I thought some of the boys had put there to scare me; then I walked a little piece towards it, and I saw what it was, and I got out of there.

?I got up the ladder, and called the police station; it was after 3 o?clock.

?I tried to get Mr. Frank, and was still trying when the (police) officers came. I guess I was trying (to get Frank to answer the telephone) about eight minutes.

?I saw Mr. Frank Sunday morning (the same morning), at about 7 or 8 o?clock. He was coming in the office. He looked down on the floor, and never spoke to me. He dropped his head down, right this way??illustrating.

?Boots Rogers, Chief Lanford, Darley, Frank and I were there when they opened the clock. Mr. Frank opened the clock, and saw the punches were all right. I punched every half hour from 6 o?clock p.m. to 3 o?clock a.m.

?On Tuesday night, April 29th, at about 10 o?clock, I had a conversation at the station house with Mr. Frank. They handcuffed me to a chair.

?The went and got Mr. Frank and brought him in, and he sat down next to the door. He dropped his head and looked down. We were all alone. I said, ?Mr. Frank, it?s mighty hard on me to handcuffed here for something that I don?t know anything about.?

?He said, ?What?s the difference? They have got me locked up, and a man guarding me.?

?I said, ?Mr. Frank, do you believe I committed this crime??

?He said, ?No, Newt, I know you didn?t; but I believe you know something about it.?

?I said, ?Mr. Frank, I don?t know a thing about it, more than finding the body.?

?He said, ?We are not talking about that now; we will let that go. If you keep that up, we will both go to hell.?

?Then the officers came in. When Mr. Frank came out of his office that Saturday (evening) he was looking down, and rubbing his hands. I had never seen him rub his hands that way before.?

Newt stated, on cross-examination, that he would not have gone so far back in the basement, and would not have seen the body, if a call of nature down there had not caused him to use the toilet which was near the corpse.

?When I got through, I picked up my lantern; I walked a few steps that way; I seed something over there, about that much of the lady?s leg and dress??illustrating.

?I think I reported to the police that it was a white woman. When I first got there, I didn?t think it was a white woman, because her face was so dirty, and her hair crinkled.

?When I was in the basement (the morning the body was found), one of the policemen read the note that they found. They read these words, ?The tall, black, slim negro did this, he will try to lay it on the night? and when they go to the word ?night,? I said, ?They must be trying to put it off on me.??

(Note that the negro is corroborated on this point by Sergeant Dobbs, the next witness; and bear it in mind because of its extreme importance?as you will soon see.)

Sergeant L.S. Dobbs testified that a call came to the police headquarters at about 3:25, on the morning of April 27th, and he went to the pencil factory, descended to the basement by means of the trap-door and ladder. The negro led the officers back to the body, about 150 feet.

?The girl was lying on her face, not directly lying on her stomach, with the left side up just a little. We couldn?t tell by looking at her whether she was white or black, only by her golden hair. They turned her over, and her face was full of dirt and dust. They took a piece of paper and rubbed the dirt off her face, and we could tell then that it was a white girl. I pulled up her clothes, and could tell by the skin of the knee that it was white girl. Her face was punctured, full of holes, and swollen and black. She had a cut on the left side of her head, as if she had been struck, and there was a little blood there. The cord was around her neck, sunk into the flesh. She also had a piece of her underclothing around her neck. The cord was still tight around her neck. The tongue was protruding just the least bit. The cord was pulled tight, and had cut into the flesh, and tied just as tight as it could be. The underclothing around the neck was not tight.

?There wasn?t much blood on her head. It was dry on the outside. I stuck my finger under the hair and it was a little moist.

?This scratch pad was lying on the ground, close to the body. I found the notes under the sawdust, lying near the head. The pad was lying near the notes. They were all right close together.

?Newt Lee told us it was a white woman.

?There was a trash pile near the boiler, where this hat was found, and paper and pencils down there, too. The hat and shoe were on the trash pile. Everything was gone off it, ribbons and all.

?It looked like she had been dragged on her face by her feet. I thought the places on her face had been made by dragging. That was a dirt floor, with cinders on it, scattered over the dirt.

?The place where I thought I saw some one dragged was right in front of the elevator, directly back. The little trail where I thought showed the body was dragged, went straight on down (from in front of the elevator) where the girl was found. It was a continuous trail.

?The body was cold and stiff. Hands folded across the breast.

?I didn?t find any blood on the ground, or on the saw dust, around where we found the body.

?The sign of dragging?started east of the ladder. A man going down the ladder to the rear of the basement, would not go in front of the elevator where the dragging was.

?A man couldn?t get down that ladder with another person. It is difficult for one person to get through that scuttle hole. The back door was shut; staple had been pulled.?

?The lock was locked still. It was a sliding door, with a bar across the door, but the bar had been taken down. It looked like the staple had been recently drawn.

?I was reading one of the notes to Lee, with the following words, ?A tall, black negro did this; he will try to lay it on the night,? and when I got to the word ?night,? Lee says, ?That means the night watchman.?

?I found the handkerchief on a sawdust pile, about ten feet from the body. It was bloody, just as it is now.

?The trap-door leading up from the basement was closed when we got there.?

City Officer John N. Starnes was the State?s next witness. He testified to reaching the factory between 5 and 6 o?clock that Sunday morning. He called up Leo Frank, and asked him to come, right away.

?He said he hadn?t had any breakfast. He asked where the night watchman was. I told him it was very necessary for him to come, and if he would come, I would send an automobile for him.

I didn?t tell him what had happened, and he didn?t ask me.

?When Frank arrived at the factory, a few minutes later, he appeared to be nervous; he was in a trembling condition. Lee was composed.

?It takes not over three minutes to walk from Marietta Street, at the corner of Forsyth Street, down to the factory.

?I chipped two places off the back door, which looked like they had bloody finger prints.?

(Let me here remind the reader, that Jim Conley, a State?s witness, could have been required by Leo Frank?s lawyers to make the imprint of his fingers while he was on the stand, and if these finger marks had resembled those made on the back door, Frank would have gone free, and the negro would have swung. The State, however, could not ask Leo Frank to make his finger-prints, for to have done so, would have been requiring him to furnish evidence against himself.

My information is that Conley?s lawyer, W.M. Smith, after he had agreed with the Burns Agency to help them fix the crime on his client, went to the convict camp, where Conley was working out his sentence, and got his finger-prints, twice.

Be that as it may, Frank?s attorneys dared not ask the negro to make the prints, when they had him on the stand.

You can draw your own conclusions.

Burns and Lehon do not amount to anything much as detectives; but even these amateurs know something of the Bertillon system; and if those finger-prints on the back door had not been Leo Frank?s, Burns and Lehon would most certainly have proven that much, by actual demonstration, and thus put the crime on Jim Conley, or upon some other person than their client, Frank.)

The next witness was W.W. Rogers. He and John Black went after Frank, following Starne?s telephone communication. Mrs. Frank opened the door, and was asked if Frank was in. He came forward, partly dressed, and asked if anything had happened at the factory. No answer being returned, he inquired, ?Did the night-watchman call up and report anything to you??

Mr. Black asked him to finish dressing, and accompany them to the factory, and see what had happened.

?Frank said that he thought he dreamt in the morning, about 3 o?clock, about hearing the telephone ring.?

Witness said Frank appeared extremely nervous, and called for a cup of coffee. He was rubbing his hands. When they had taken their seats in the automobile, one of the officers asked him if he knew a little girl named Mary Phagan.

Frank answered, ?Does she work at the factory??

Rogers said, ?I think she does?; and Frank added, ?I cannot tell whether she works there or not, until I look at my pay-roll book. I know very few of the girls that work there. I pay them off but I very seldom go back in the factory.?

The witness spoke of Frank?s conduct at the morgue, and although the purpose of taking him there was to have him view the corpse, the witness never saw Frank look at it, but did see him step away into a side room.

From the morgue, the party went to the pencil factory, where Frank opened the safe, took out his time-book, consulted it, and said: ?Yes, Mary Phagan worked here. She was here yesterday to get her pay.?

He said: ?I will tell you about the exact time she left here. My stenographer left about 12 o?clock, and a few minutes after she left, the office boy left, and Mary came in and got her pay and left.?

(Note, later on, that other girls were at Frank?s office, the same Saturday morning, and that he nevertheless fixed the exact time of the arrival of the girl he did not know. And he fixed it right.)

?He then wanted to see where the girl was found. Mr. Frank went around to the elevator, where there was a switch box on the wall, and put the switch in. The box was not locked. As to what Mr. Frank said about the murder, I don?t know that I heard him express himself, except down in the basement.

The officers showed him where the body was found, and he made the remark that it was too bad, or something like that.?

(Frank was not under arrest at this time, and Newt Lee was. Nothing, as yet, had been said about Conley.)

On cross-examination, the witness stated that ?we didn?t know it was a white girl or not until we rubbed the dirt from the child?s face, and pulled down her stocking a little piece. The tongue was not sticking out; it was wedged between her teeth. She had dirt in her eye and mouth. The cord around her neck was drawn so tight it was sunk in her flesh, and the piece of underskirt was loose over her hair.

?She was lying on her face, with her hands folded up. One of her eyes was blackened. There were several little scratches on her face. A bruise on the left side of her head, some dry blood in her hair.

?There was some excrement in the elevator shaft. When we went down on the elevator, the elevator mashed it. You could smell it all around.

?No one could have seen the body at the morgue unless he was somewhere near me. I was inside, and Mr. Frank never came into that little room, where the corpse lay. When the face was turned toward me, Mr. Frank stepped out of my vision in the direction of Mr. Gheesling?s (the undertaker?s) sleeping room.?

Miss Grace Hicks testified that she worked on the second floor at the factory. Mary Phagan?s machine was right next to the dressing room, and in going to the closet, the men who worked on that floor passed within two or three feet of Mary. Between the closet of the men and of the women, there was ?just a partition.?

The witness had identified the body at the morgue early Sunday morning, April 27th. ?I knew her by her hair. She was fair-skinned, had light hair, blue eyes, and was heavy built, well developed for her age. She weighed about 115 pounds. Magnolia Kennedy?s hair is nearly the color of Mary Phagan?s?.?

John R. Black, the next witness for the State, testified that he went with Rogers to Frank?s house. ?Mrs. Frank came to the door; she had on a bathrobe. I started that I would like to see Mr. Frank, and about that time Mr. Frank stepped out from behind a curtain. His voice was hoarse and trembling and nervous and excited. He looked to me like he was pale. He seemed nervous in handling his collar; he could not get his tie tied, and talked very rapid in asking what had happened. He kept on insisting for a cup of coffee.

?When we got into the automobile, Mr. Frank wanted to know what had happened at the factory, and I asked him if he knew Mary Phagan, and told him she had been found dead in the basement. Mr. Frank said he did not know any girl by the name of Mary Phagan, that he knew very few of the employees.

?In the undertaking establishment, Mr. Frank looked at her; he gave a casual glance at her, and stepped aside; I couldn?t say whether he saw the face of the girl or not. There was a curtain hanging near the room, and Mr. Frank stepped behind the curtain.

?Mr. Frank stated, as we left the undertaker?s, that he didn?t know the girl, but he believed he had paid her off on Saturday. He thought he recognized her being at the factory Saturday by the dress that she wore.

At the factory, Mr. Frank took the slip out (of the time clock), looked over it, and said it had been punched correctly. (That is, the slip showed that Newt Lee had punched every half-hour during the night before.)

?On Monday and Tuesday following, Mr. Frank stated that the clock had been mispunched three times.

?I saw Frank take it out of the clock, and went with it back toward his office.

?When Mr. Frank was down at the police station, on Monday morning (the next after the corpse was found), Mr. Rosser and Mr. Haas were there. Mr. Haas stated, in Frank?s presence, that he was Frank?s attorney. This was about 8, or 8:30 Monday morning. That?s the first time he had counsel with him.?

(Observe that the Jews employed the best legal talent, before the Gentiles had even suspected Frank?s guilt.

Why did his rich Jewish connections feel so sure of his need of eminent lawyers, that they employed Rosser, evidently on Sunday, since city lawyers do not open their offices before 8 o?clock.)

?Mr. Frank was nervous Monday; after his release, he seemed very jovial.

?On Tuesday night, Frank said, at the station house, that there was nobody at the factory at 6 o?clock but Newt Lee, and that Newt Lee ought to know more about it, as it was his duty to look over the factory every thirty minutes.?

(Note Frank?s deliberate direction of suspicion to the ?tall, slim night-watch,? upon whom the notes place the crime. Frank was virtually telling the police the same thing that the notes told, viz., that Newt Lee committed the crime.)

?On Tuesday night, Mr. Scott and myself suggested to Mr. Frank to talk to Newt Lee. They went in a room, and stayed about five or ten minutes, alone. I couldn?t hear enough to swear that I understood what was said. Mr. Frank said that Newt stuck to the story that he knew nothing about it.

?Mr. Frank stated that Mr. Gantt was there on Saturday evening, and that he told Lee to let him get the shoes, but to watch him, as he knew the surroundings of the office.

?After this conversation Gantt was arrested.?

(Observe that Frank?s allusion to Gantt could have had no other purpose than to direct suspicion toward him; and that, while Frank was seeking to involve two innocent men, he did not breathe a suspicion of Jim Conley, whom he knew to have been in the factory when Mary Phagan came for her pay.)

After the visit to the morgue, the party went to the factory, where Frank got the book, ran his finger down until he came to the name of Mary Phagan, and said: ?Yes, this little girl worked here, and I paid her $1.20 yesterday.?

?We went all over the factory. Nobody saw that blood spot that morning.?

Mr. Haas, as Frank?s attorney, had told witness to go out to Frank?s house, and search for the clothes he had worn the week before, and the laundry, too.

Frank went with them, and showed them the dirty linen.

?I examined Newt Lee?s house. I found a bloody shirt at the bottom of a clothes barrel there, on Tuesday morning, about 9 o?clock.?

On re-direct examination, the witness stated that Frank said, after looking over the time sheet, and seeing that it had not been punched correctly, that it would have given Lee an hour to have gone out to his house and back.?

(Evidently, Frank knew where this negro lived, and how long it required for him to go home that Saturday night, and return to the factory where the girl?s body lay. This new time-slip gave Newt an hour unaccounted for; and, in connection with the bloody shirt, the new time-slip began to make the case look ugly for Newt, ?the tall, slim night-watch,? whom the writer of the notes accused.)

J.M. Gantt was next put up by the State, and his evidence, in substance, was:

That he had been shipping clerk and time-keeper at the pencil factory, and that Frank had discharged him on April 7th, for an alleged shortage of $2 in the pay-roll.

He had known Mary Phagan since she was a little girl, and that Frank knew her, too.

One Saturday afternoon, she came in the office to have her time corrected, by Gantt, and after Gantt had gotten through with her, Mr. Frank came in and said: ?You seem to know Mary pretty well.?

After Gantt was discharged, he went back to the factory on two occasions. ?Mr. Frank saw me both times. He made no objections to my going there.?

One girl used to get the pay envelope for another, with Frank?s knowledge. Gantt swore he knew nothing of how the $2 shortage in the pay roll occurred. Frank discharged him because Gantt refused to make it good.

Gantt described how Frank had behaved at 6 o?clock Saturday evening when he, Gantt, went for his shoes. Standing at the front door, Gantt saw Frank coming down the stairs, and when Frank saw Gantt, ?he kind of stepped back, like he was going to go back, but when he looked up and saw I was looking at him, he came on out, and I said, ?Howdy, Mr. Frank,? and he sorter jumped again.?

Then Gantt asked permission to go up for his shoes, and Frank hesitated, studied a little, inquired the kind of shoes, was told they were tans, and stated that he thought he had seen a negro sweep them out. But when Gantt said he left a black pair, also, Frank ?studied? a little bit, and told Newt to go with Gantt, and stay with him till he got his shoes. Gantt went up, and found both pair, right where he had left them.

?Mr. Frank looked pale, hung his head, and kind of hesitated and stuttered, like he didn?t like me in there, somehow or other.?

(On the strength of what Frank insinuated against Gantt, he was arrested before Frank was, and not released until Thursday night.)

Mrs. J.A. White, sworn for the State, said that she went to the factory to see her husband, who was at work there, on April 26th. She went at 11:30, and stayed till 11:50, when she left. She returned about 12:30, and saw Frank standing before the safe, in his outer office. ?I asked him if Mr. White had gone back to work; he jumped, like I surprised him, and turned and said, ?Yes.??

She went up stairs to see her husband, and while she was up there, about 1 o?clock, Frank came up and told Mr. White that if she wanted to get out before 3 o?clock, she had better come down, as he was going to leave, and lock the door, and that she had better be ready by the time he could get his coat and hat.

Mrs. White testified to this tremendously important fact:

?As I was going on down the steps, I saw a negro sitting on a box, close to the stairway on the first floor.

?Mr. Frank did not have his coat or hat on when I passed out.?

On cross-examination, this lady swore: ?I saw a negro sitting between the stairway and the door, about five or six feet from the foot of the stairway.?

While Mrs. White was talking to her husband, between 11:30 and 11:50, she saw Miss Corinthia Hall and Mrs. Emma Freeman there, and they left before she did.

(Mrs. White did not work at the factory, and did not know Jim Conley. The place where she saw a negro sitting, was where Jim sat when he had nothing else to do. Picture to yourself the interior of the factory, as Mrs. White departs at about 1 o?clock that fatal Saturday.

Two carpenters are at work on the fourth floor, tearing out a partition and putting up a new one, and they are 40 feet back from the elevator.

Frank is sitting on the second floor, near the head of the stairs; and Jim Conley is seated at the foot of the same stairs, on the floor below, not more than thirty feet from his white boss.

The lady passes on out, leaving these two men practically together. According to his own statement to the police officers, Frank has already had Mary Phagan, in his office, in his possession, between the first departure of Mrs. White at 11:50 and her second coming at 12:30!

Frank?s own admission put the girl alone with him in his private office, shortly after the noon hour; and when Mrs. White returns at 30 minutes after the noon hour, the girl is nowhere to be seen.

Who can account for Mary between these times? And who can account for Frank?

Here is the tragedy, hemmed within the first departure and the second arrival of Mrs. White?a space which could not be filled by any two human beings, excepting Jim Conley and Leo Frank.

(We will see, later, how each of the two filled it.)

Harry Scott, the State?s next witness, was Superintendent of the local branch of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. He was employed by Frank for the pencil factory.

In Frank?s private office, Monday afternoon, April 28th, the detective heard Frank?s detailed account of his movements the Saturday before. Frank told of his going to Montag?s, and of the coming of Mrs. White.

?He then stated that Mary Phagan came into the factory at 12:10 p.m., to draw her pay; that she had been laid off the Monday previous, and she was paid $1.20, and that he paid her off in his inside office, where he was at his desk, and when she left his office and went into the outer office she had reached the outer office door, leading into the hall, and turned around to Mr. Frank and asked if the metal had come yet. Mr. Frank replied that he didn?t know, and that Mary Phagan, he thought, reached the stairway, and he heard voices, but he couldn?t distinguish whether they were men or girls talking.?

Later, a witness stated that it was before Mary came that Frank said he heard voices?before 12 o?clock.

(Let me explain that Mary worked on Frank?s floor, some distance back of his office, and that she placed metal tips on the pencils. The supply of this metal gave out, and more was ordered, but in the meantime Mary was unemployed. Her question, ?Has the metal come?? was therefore equivalent to, ?Will there be work for me next Monday??

Note particularly that in his private conference with his own detective, he did not pretend that he had not known Mary Phagan. On the contrary, see what Scott says further on.)

?He (Frank) also stated, during our conversation, that Gantt knew Mary Phagan very well, and that he was familiar and intimate with her. He seemed to lay special stress on it, at the time. He said that Gantt paid a good deal of attention to her.?

(The morning before, he did not know her, and had to consult his book! Although he had passed within three feet of her, every day when he went to the toilet, and had paid her off every week, for about a year, he did not know any girl of that name!)

Mr. Herbert J. Haas (later the Chairman of the Frank Finance Committee) told the detective to report to him, first, before letting the public know ?what evidence we had gathered. We told him we would withdraw from the case before we would adopt any practice of that sort.?

Scott asked Frank to use his influence as employer with Newt Lee, and to try to get him to tell what he knew. Frank consented, and the two were put in a private room, in order that Frank might get something out of the ?tall, slim night-watch.?

?When about ten minutes was up, Mr. Black and I entered the room, and Lee hadn?t finished his conversation with Frank, and was saying: ?Mr. Frank, it is awful hard for me to remain handcuffed to this chair, and Frank hung his head the entire time the negro was talking to him, and finally, in about thirty seconds, he said, ?Well, they have got me, too,? After that, we asked Mr. Frank if he had gotten anything out of the negro, and he said, ?No, Lee still sticks to his original story.?

?Mr. Frank was extremely nervous at that time. He was very squirmy in his chair, crossing one leg after the other, and didn?t know where to put his hands; he was moving them up and down his face, and he hung his head a great deal of the time while the negro was talking to him. He breathed very heavily, and took deep swallows, and hesitated somewhat. His eyes were about the same as they are now.

?That interview between Lee and Frank took place shortly after midnight, Wednesday, April 30. On Monday afternoon, Frank said to me that the first punch on Newt Lee?s slip was 6:33 p.m., and his last punch was 3 a.m. Sunday. He didn?t say anything at that time about there being any error in Lee?s punches. Mr. Black and I took Mr. Frank into custody about 11:30 a.m. Tuesday, April 29th.

?His hands were quivering very much, he was very pale. On Sunday, May 3, I went to Frank?s cell at the jail with Black, and I asked Mr. Frank if, from the time he arrived at the factory from Montag Bros.?, up until 12:50 p.m., the time he went upstairs to the fourth floor, was he inside of his office the entire time, and he stated, ?Yes.?

?Then I asked him if he was inside his office every minute from 12 o?clock until 12:30, and he said, ?Yes.?

?I made a very thorough search of the area around the elevator and radiator, and back in there. I made a surface search; I found nothing at all. I found no ribbon or purse, or pay envelope, or bludgeon or stick. I spent a great deal of time around the trap door, and I remember running the light around the doorway, right close to the elevator, looking for splotches of blood, but I found nothing.?

(No effort was made to impeach Harry Scott, and the whole brunt of Rosser?s cross-examination was to compel the witness to admit that Frank answered the girl?s question about the metal, by saying, ?No,? instead of, ?I don?t know.?[/justify]

[/center]

[/center] American Dissident Voices broadcast of April 26, 2014

American Dissident Voices broadcast of April 26, 2014 Mary met Frank in his office and asked for her pay. She also asked Frank if the supply of metal had come in, since, if it hadn?t, she wouldn?t work on Monday. Frank said ?I don?t know,? and asked Mary to accompany him to the metal room, further back on the same floor, to see. Back they went, the lustful monster with evil intent, and the innocent girl, dressed up brightly for the holiday, taking the last steps of her life.

Mary met Frank in his office and asked for her pay. She also asked Frank if the supply of metal had come in, since, if it hadn?t, she wouldn?t work on Monday. Frank said ?I don?t know,? and asked Mary to accompany him to the metal room, further back on the same floor, to see. Back they went, the lustful monster with evil intent, and the innocent girl, dressed up brightly for the holiday, taking the last steps of her life.

American Dissident Voices broadcast of May 3, 2014

American Dissident Voices broadcast of May 3, 2014 [justify]by Thomas E. Watson (pictured), Watson?s Magazine, Volume 21 Number 5, September 1915

[justify]by Thomas E. Watson (pictured), Watson?s Magazine, Volume 21 Number 5, September 1915 [justify]Dr. H.F. Harris, a practicing physician, testified:

[justify]Dr. H.F. Harris, a practicing physician, testified: [justify]Harry Scott, recalled:

[justify]Harry Scott, recalled: [justify]He told of how Frank would signal to him, by ?stomping? on the floor, when a woman was alone with Frank, and how he, Jim, was then to lock the door. When Frank got through with his woman, he would whistle, and Jim would unlock the door.

[justify]He told of how Frank would signal to him, by ?stomping? on the floor, when a woman was alone with Frank, and how he, Jim, was then to lock the door. When Frank got through with his woman, he would whistle, and Jim would unlock the door.