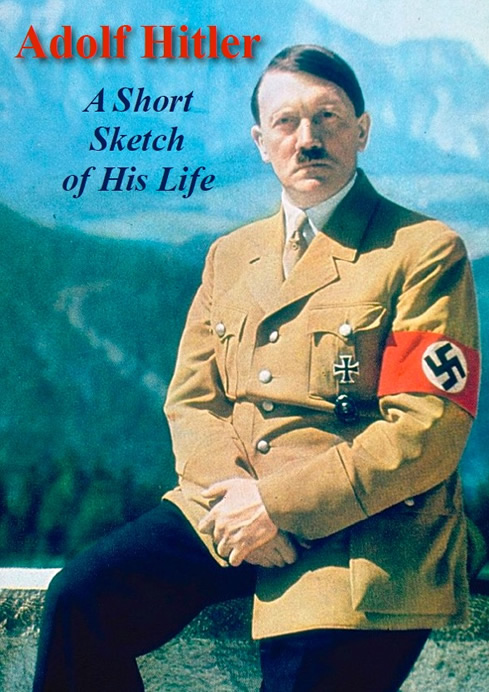

Philipp Bouhler - Adolf Hitler A short sketch of his life

Introduction

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, at Braunau in Upper Austria, close to the Bavarian frontier. Because it is situated on the frontier that divided two branches of the German people, Hitler has spoken of Braunau as representing for him “The Symbol of a Great Task”, namely that of uniting all Germans in one State. His father, who was the son of poor peasants from the forest district, had worked himself upwards through his own study and perseverance until he became a civil servant. At the time that Adolf was born his father was Customs Officer at Braunau. Being proud of his own achievement and the status he had reached, his dearest desire was that his son should also enter the civil service; but the son was entirely opposed to this idea.

He would be an artist.

When he was thirteen years old Hitler lost his father and four years later his mother died. So that he found himself alone in the world at the age of seventeen. He had attended the primary school and subsequently the grammar school at Linz; but poverty forced him to give up his studies and earn his bread. He went to Vienna, with the intention of studying to be an architect but he had to work for his livelihood as manual labourer at the building trade, where he mixed the mortar and served the carpenters and bricklayers. Later on he earned a daily pittance as an architectural draughtsman. Having to depend entirely on himself, he experienced in his own person from his earliest years what poverty and hunger and privation meant, And so he shared the daily fate of the workers, the “proletariat” in the building trade, and felt where the shoe pinched. Thus it came about that he began to think in terms of social reform during his early years.

He busied himself with the political questions of the day. In this study he was influenced by the personality of Schoenerer, the leader of the Pan-German Austrians, and Lueger, who was the Vienna Burgermeister and founder of the Christian-Social Party. Hitler conceived a great admiration for these two men. He made an exhaustive study of the teachings of Karl Marx and here came to the important conclusion that one had to know Judaism in order to have the key to an inner and real knowledge of what Social Democracy meant.

At the building site where he worked he came into contact with Social Democracy for the first time. He at once began to make a careful study of the literature dealing with it and thus acquired a detailed knowledge of the Marxist programme and the ways and means which were proposed to put it into practice. This led to controversies with his fellow workers. And he refused to join their organization. At that time he did not believe in the idea that the trade-unions were an appropriate means of protecting the interests of the working classes against the arbitrary importunities of the employers. He only saw that the political attitude of the trade-unions was Marxist and he considered the tradeunionist idea as definitely identical with that of Marxism, while he looked on Marxism as something that would destroy all civilization.

His fellow workers threatened to fling him down from the scaffolding.

They succeeded in forcing him to give up his job. In his next job he had to go through much the same experience. But as he acquired a more thorough understanding of the character and tendencies of his opponents his influence on the other workmen increased and he soon realized how they reacted to his different view of things. He then saw clearly that the German worker was by no means a bad fellow in himself, that he was not anti-national and that he was only the victim of unscrupulous agitators.

Though the years spent in Vienna meant a hard and bitter struggle with life, the experience gained in this school was of inestimable value afterwards. Hitler was now yearning to live as a German in Germany itself, free from the oppression under which the German element had to suffer in that potpourri of nations which made up the Habsburg Empire. So he left Vienna and came to live in Munich. That was on April 24, 1912.

In those days Munich was the chief centre of artistic and cultural life in Germany. Still hoping to make a name for himself as an architect, Adolf Hitler now devoted as much time and energy as possible to the study of architecture, while at the same time he had to earn his daily bread by designing and colouring placards. Recently he had been doing a good deal of reading for purposes of self-education. He continued this during his artistic studies and work in Munich, making history his speciality, which had been his favourite subject at school.

But he went further than this, for he literally denied himself food in order to save the money for visits to the theatre and hearing Grand Opera, especially the music dramas of Richard Wagner, whom he revered as a German artist and reformer in the grand style. It was especially during those years that Hitler laid the foundations of that all round knowledge which surprises everybody with whom he discusses general questions today.

August 2, 1914 arrived. A spirit of fervid but solemn enthusiasm ran through the whole nation. Wave after wave of German youth rushed enthusiastically to join the volunteer regiments and reserve battalions.

Hitler, who had always felt that he was a German first and foremost, presented himself at the headquarters of one of the Bavarian regiments and volunteered for the front. He regarded this act as a matter of course. Nor were there any technical difficulties in the way; for in the February of that year he had been definitely exempted from the obligation of military service in Austria. On October 10, 1914, he left for the front as a soldier in the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment.

Destiny seemed to have preordained that Hitler should serve in the old German Army, that organization which was a magnificent example of the folk community and which he had for a long time envisaged as the kind of social formation through which the German people would finally reach its destined goal.

Adolf Hitler threw himself body and soul into the work of his new calling as a soldier. He received his baptism of fire in Flanders, where he faced death in the ranks of that regiment which was made up of German youth who stormed the trenches and fought and fell while they sang Deutschland ueber alles. During the attack on the Bayernwald and in the subsequent engagements around Wytschaete Hitler showed remarkable bravery; so much so that already on December 2, 1914, less than two months after he had first entered the trenches, he was awarded the Iron Cross of the Second Class. Having shown himself resourceful and courageous, without being foolhardy, he was now given one of the most hazardous jobs in the regiment, namely that of dispatch-runner, for which only picked soldiers are used. In carrying out this task he won a good deal of admiration, especially because on more than one occasion he voluntarily stepped in and took on himself a piece of dangerous work which otherwise would have fallen to the lot of older men who had wives and families at home. On the whole it can be said without any fear of contradiction that Hitler’s conduct as a soldier won the unstinted admiration of his superiors; while his companions in the trenches, no matter how opposed their political views were to his, admired his courage and his genuine spirit of comradeship.

On October 6, 1916, he was wounded in the thigh by a shrapnel splinter and had to be sent to one of the home hospitals for treatment. Within a few months he was on his feet again. He left hospital in March 1917 and immediately volunteered once more for the front.

During the great offensive of 1918, while carrying dispatches, he succeeded in ambushing a French officer and about fifteen men and brought them back prisoners. For this he was awarded the Iron Cross of the First Class.

On the night of October 13/14, 1918, the British launched an attack

with phosgene gas in the sector south of Ypres. Hitler’s regiment suffered severely and the casualties were extremely heavy. Hitler himself suddenly felt an excruciating pain in the eyes as he was returning with a dispatch to his own lines. He managed to struggle back however and deliver his dispatch. After that he was sent to hospital, totally blind.

While the German armies were still fighting desperately on all fronts for the very existence of their native land, defeatism was at work behind the lines and at home. Under the corroding influence of the propagandist poison spread by anti-national agencies at home, civilian morale was steadily crumbling. This process of disintegration gradually reached the soldiers at the front, where it took on a graver character day after day. The coming downfall cast its darkening shadow even across the fighting lines.

The revolt of the sailors at the naval base in Kiel was the signal for the revolution. On November 9, 1918, the day of the general collapse had come. It was not merely the monarchical constitution in Germany that was overthrown. No, but everything else with it — the Fatherland itself, faith in the Fatherland and in, one’s fellow man, order and discipline.

Hitler was in hospital at Pasewalk in Pomerania when he first heard the news. The pain in the eyes had gradually become less severe. His sight began to return and he now had hopes of regaining his normal powers of vision. The impression which the news then made was described by him some years later in the following words :

“So all had been in vain. In vain all the sacrifices and privations, in vain the hunger and thirst for endless months, in vain those hours that we stuck to our posts when the fear of death gripped our souls, and in vain the deaths of two millions who fell in the fulfilment of their duty. Think of those hundreds of thousands who set out with hearts full of faith in their Fatherland, and never returned; ought not their graves to open so that the spirits of those heroes bespattered with mud and blood should come home and wreak their vengeance on those who had despicably betrayed the greatest sacrifice which a human being can make for his country.

Was it for this that the soldiers gave their lives in August and September 1914, for this that the volunteer regiments followed the old comrades m the autumn of the same year? Was it for this that those boys of seventeen years of age were mingled with the soil of Flanders? Was this meant to be the fruits of the sacrifice which German mothers made for their Fatherland when, with heavy hearts, they said goodbye to their sons, who never returned ? Was all this done in order to enable a gang of despicable criminals to lay hands on the Fatherland ?”

Hitler now developed a burning hatred against the perpetrators of what he considered to be a most dastardly crime and at the same time it became apparent to him that Fate had destined him for a certain task.

On that day he decided to take up political work.

Philipp Bouhler - Adolf Hitler Das werden einer volksbewegung

Philipp Bouhler - Bitka za Njemačku

Adolf Hitler - Videos

Adolf Hitler - PDF

Führer - PDF

Le Révérend Père Augustin Berthe (1830-1907) est né à Merville, dans le diocèse de Cambrai. Ordonné prêtre en 1854, il devient missionnaire et prédicateur de la Congrégation du Plus Saint Rédempteur, à l’intérieur de l’Église catholique. Professeur de rhétorique, recteur de diverses maisons rédemptoristes en France, il est nommé avocat général de la Congrégation à Rome où il finira sa vie. Il a écrit de nombreux articles et ouvrages, traduits en plusieurs langues, en particulier une biographie de Garcia Moreno, président de l’Équateur dont il fut le secrétaire.

Le Révérend Père Augustin Berthe (1830-1907) est né à Merville, dans le diocèse de Cambrai. Ordonné prêtre en 1854, il devient missionnaire et prédicateur de la Congrégation du Plus Saint Rédempteur, à l’intérieur de l’Église catholique. Professeur de rhétorique, recteur de diverses maisons rédemptoristes en France, il est nommé avocat général de la Congrégation à Rome où il finira sa vie. Il a écrit de nombreux articles et ouvrages, traduits en plusieurs langues, en particulier une biographie de Garcia Moreno, président de l’Équateur dont il fut le secrétaire.

The Enemy of Europe by Francis Parker Yockey was originally written in the early 1950s as sequel to his most important work Imperium (1948).

The Enemy of Europe by Francis Parker Yockey was originally written in the early 1950s as sequel to his most important work Imperium (1948).

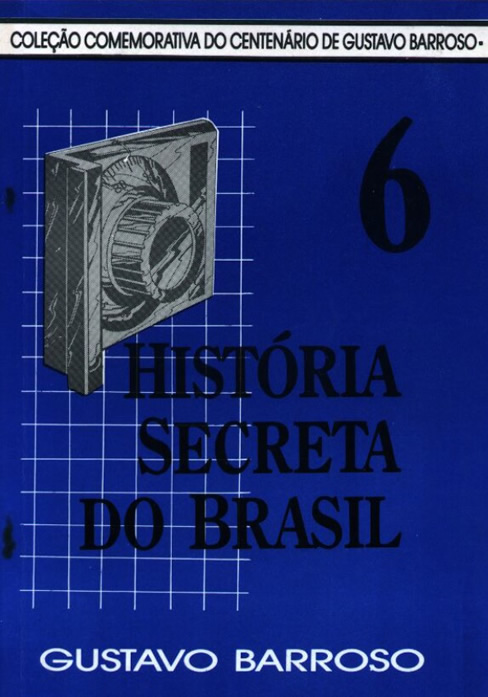

São seis volumes RAROS escritos pelo advogado, contista, ensaísta, político e romancista fortalezense Gustavo Barroso (1888-1923).

São seis volumes RAROS escritos pelo advogado, contista, ensaísta, político e romancista fortalezense Gustavo Barroso (1888-1923).

Harold James Jenks practically grew up behind bars spending all of his teenage years in jails, reformatories and prisons. Jenks was not free until he was 24 years old-learned how to fight as a matter of survival. On the "outside" Jenks used knowledge acquired in prison for jobs managing unruly customers in nightclubs, etc. - getting upwards of $500 a day for occasional "trouble-shooting."

Harold James Jenks practically grew up behind bars spending all of his teenage years in jails, reformatories and prisons. Jenks was not free until he was 24 years old-learned how to fight as a matter of survival. On the "outside" Jenks used knowledge acquired in prison for jobs managing unruly customers in nightclubs, etc. - getting upwards of $500 a day for occasional "trouble-shooting." Michael H. Brown served in the U.S. Army Airborne, 101st and 82nd (2 years each) 1960-1964. Lead paramilitary attack against pro-Communist rioters in San Francisco during 1966.

Michael H. Brown served in the U.S. Army Airborne, 101st and 82nd (2 years each) 1960-1964. Lead paramilitary attack against pro-Communist rioters in San Francisco during 1966.